- Home

- History

- Community

- Organizations

- Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association

- Victoria Chinese Canadian Veterans Association

- Chinese Public School

- Clan Associations

- County Assocations

- Dialect Assocations

- Friendship Associations

- Political Organizations

- Recreational Associations

- Religious Organizations

- Women's Associations

- Other Organizations

- People

- Resources

- Contact

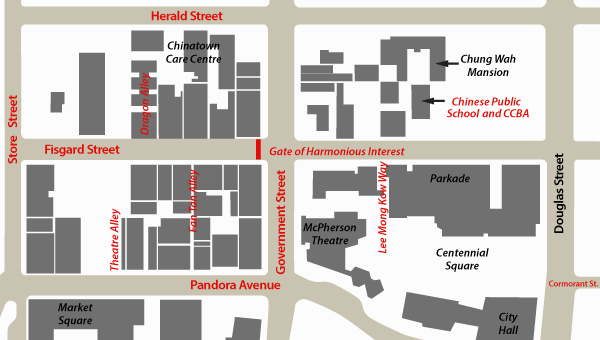

Fan Tan Alley

The link from the past to the present centre of Chinatown

Fan Tan Alley is named after a gambling game that reached the height of its popularity in this location in the early 1940s. The game is named after its component parts: “Fan” being to turn over, and “Tan” meaning to spread out. The dealer takes a handful of buttons or beads and covers them with a brass cup. The players bet on how many buttons will be left after the dealer has removed all multiples of four. Once the bets are made, the dealer turns over the cup and spreads out the buttons to count them.

Looking north into Fan Tan Alley from Pandora Avenue. On the left is the Loo Chew Fan Building and on the right, the Macdonald Building (Photo by Charles Yang, 2011).

On the south side of Fisgard, the Loo Tai Cho and Sheam and Lea buildings flank the entrance to Fan Tan Alley. Sheam Tip and Low Yan San built the first section of the Sheam and Lee Building in 1888. The property changed hands several times and was leased in 1901 by Lee Mong Kow, a government interpreter and educator who then built a western addition to this building. On your left as you enter Fan Tan Alley is a three storey building constructed by Loo Tai Cho in 1893. There is an entry way through the corner, and some of the upper windows open onto iron balconies.

Fan Tan Alley is a very narrow lane, three to six feet wide and 240 feet long, that runs between Fisgard Street and Pandora Avenue (formerly Cormorant Street). It came into being between 1885 and 1920 as Chinese and Western landowners initially constructed buildings fronting on Fisgard and Cormorant, then over time filled in the spaces behind with new buildings. This was a popular location for opium factories, housed in wood-frame buildings behind the street-front brick buildings, and owned by Tai Soong, Kwong Lee and Shon Yuen. Until 1908, it was legal to produce opium in Canada, largely because municipal and federal governments could collect license fees and taxes. Around the turn of the twentieth century, moral reformers began to voice their concerns about opium use in Canada. As a result of actions by Western reformers and the Chinese Anti-Opium League, as well as a report by future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, opium was made illegal in Canada in 1908 and factories were shut down.

In Fan Tan Alley, looking south towards Pandora Avenue (Photo by Charles Yang, 2012). From 1910 to 1920, the construction of brick buildings between Cormorant (now Pandora) and Fisgard created the walls of Fan Tan Alley.

New brick structures were built to replace the defunct opium dens in the 1910s and 1920s and the narrow space between the buildings became known as Fan Tan Xiang (Fan Tan Alley) because of the gambling clubs that operated there from the 1910s. Since this gambling was not legal, police carried out raids on the alley. To protect the gamblers, wooden doors sealed the ends of the alley and watchmen decided whom to let in and out. Buildings contained secret escape routes in case of raids. The Fan Tan Guan (gambling clubs), cafes and restaurants of the alley were most popular in the 1940s. Once the Japanese occupied Hong Kong in 1941, Chinese men in Canada could not visit China nor send money home, so they had extra cash to spend.

Businesses in Fan Tan Alley in 2011. The alley has become a popular artists’ quarter and tourist destination thanks to revitalization efforts spearheaded by David Chuenyan Lai in the 1970s and 1980s (Photo by Charles Yang, 2011).

When the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (Exclusion Act) was lifted in 1947, Chinese men could finally bring their wives and children to Canada, and their focus shifted to spending time with their families. Police crackdowns and declining attendance led to the closure of gambling clubs in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1970s, unmaintained buildings along the alley were condemned. Historical geographer David Chuenyan Lai, who played a leadership role in the revitalization of Chinatown in the late 1970s and 1980s, recommended that the city offer low rent in the alley to emerging artists in exchange for their labour in helping to renovate these premises. As a result of the success of this initiative, Fan Tan Alley is currently a popular tourist spot containing a number of small businesses.

Sources

Lai, David Chuenyan. Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1988.

Lai, David Chuenyan. The Forbidden City within Victoria: Myth, Symbol and Streetscape of Victoria’s Earliest Chinatown. Victoria: Orca Book Publishers, 1991.

Roy, Patricia. A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989.